By Annie Greenberg

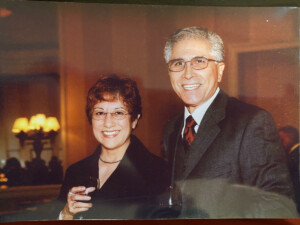

Patrick Escalera, 35, has been a caregiver for most of his adult life. His mother, Mary, was diagnosed with dementia in 2012, and his father, Tino, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2013.

When his father passed away the following year, Patrick became his mother’s primary care partner. It was only then that he realized how far her dementia had progressed.

“I never knew what Alzheimer’s entailed. I knew something was wrong with my mom and that she had dementia,” explains the Tierrasanta resident. “But we didn’t talk about it … it was kind of a cultural thing. We didn’t discuss much. I didn’t realize the gravity of what this disease does until my dad passed.”

Patrick is one of the growing number of millennials serving as dementia caregivers. According to a study by UsAgainstAlzheimer’s and USC, about one out of six millennial caregivers is caring for someone living with dementia. Roughly 42% of millennial dementia caregivers are sole caregivers and 79% reported that accessing affordable outside help was very difficult.

Unsurprisingly, 79% of millennial dementia caregivers feel emotional distress from caregiving. About 50% of millennial dementia caregivers stated that caregiving interfered with work, and 33% reported severe interference with work such as cutting back hours, losing job benefits, or being fired.

RELATED | Get free support from Alzheimer’s San Diego >>

Patrick realized early on that to be a good care partner to his mother, his life was going to have to change.

“The first three to six months after my dad passed, it wasn’t too bad. But after six months, things really started to get hard,” he says. “How am I going to work full-time when she’s leaving the stove on, forgetting to lock doors, and getting lost?”

“The first three to six months after my dad passed, it wasn’t too bad. But after six months, things really started to get hard,” he says. “How am I going to work full-time when she’s leaving the stove on, forgetting to lock doors, and getting lost?”

At the time, Patrick was working as a graphic designer. He was able to start working remotely, and then went from working full-time to part-time. Eventually, he quit his job and enrolled in the In-Home Support Services (IHSS) Program, so he could continue caring for his mother at home.

“Being able to accept help is a big thing. I have a lot of pride, but pride won’t help in the long run – it will only make things harder,” he says. “When it came to this disease, I wish my dad wasn’t so reserved. It would have been nice to know and be able to help him take care of her. A lot of people downplay the severity of dementia. It’s scary to admit and accept, but it’s easier once you have the ability to talk about it. You find out there are more people who want to be there for you, who have compassion. You can’t deal with this alone, there’s no way.”

Looking back, Patrick says he’s learned to laugh at some challenges that might have once upset or frustrated him.

Looking back, Patrick says he’s learned to laugh at some challenges that might have once upset or frustrated him.

“There are moments of levity that are so silly and absurd. For a few months, she went through a phase where she would rock a baseball cap backwards. It wouldn’t go with any outfits I’d put together. She’d even sleep with it, she just wouldn’t let it go,” he shares with a chuckle. “Mom decided to wash the coffee filters. At this point I was sitting there baffled, but I was like … okay, whatever, just go with it! You have to laugh.”

Patrick is grateful for the support he’s received from his friends and family, which has allowed him to take critical breaks from caregiving. He says he’s learned that family will be there if you allow them to be.

Mary is now in the late stages of Alzheimer’s and has been receiving in-home hospice care. They’ve been able to provide helpful tools such as a hospital bed and shower chair. Patrick is thankful he has been able to care for her in her own home, which he knows was important to her.

“My mom was a very feisty, stubborn, headstrong lady. She was very blunt and in hindsight I’m grateful because I’m not afraid of tough truths. She made me resilient, and through this disease she’s made me even more resilient,” he says.

“Being a caregiver isn’t easy, and you can be tough on yourself and unforgiving when you make mistakes. But if you are doing these things with a pure heart, the people you’re doing this for – whether they can acknowledge it or not – appreciate it. You always feel like it’s unnoticed, but it matters. And somebody has to do it.”

Need support? Our Clinical Care Coaches can help. Contact Alzheimer’s San Diego to learn about caregiving strategies, local resources like IHSS, and more. Give us a call: 858.492.4400.